Langsam – Allegro risoluto ma non troppo

Nachtmusik I – Allegro moderato. Molto moderato (Andante)

Scherzo – Schattenhaft. Fließend aber nicht zu schnell - [Shadowy. Flowing but not too fast]

Nachtmusik II – Andante amoroso

Rondo-Finale: Allegro ordinario-Allegro moderato ma energico.

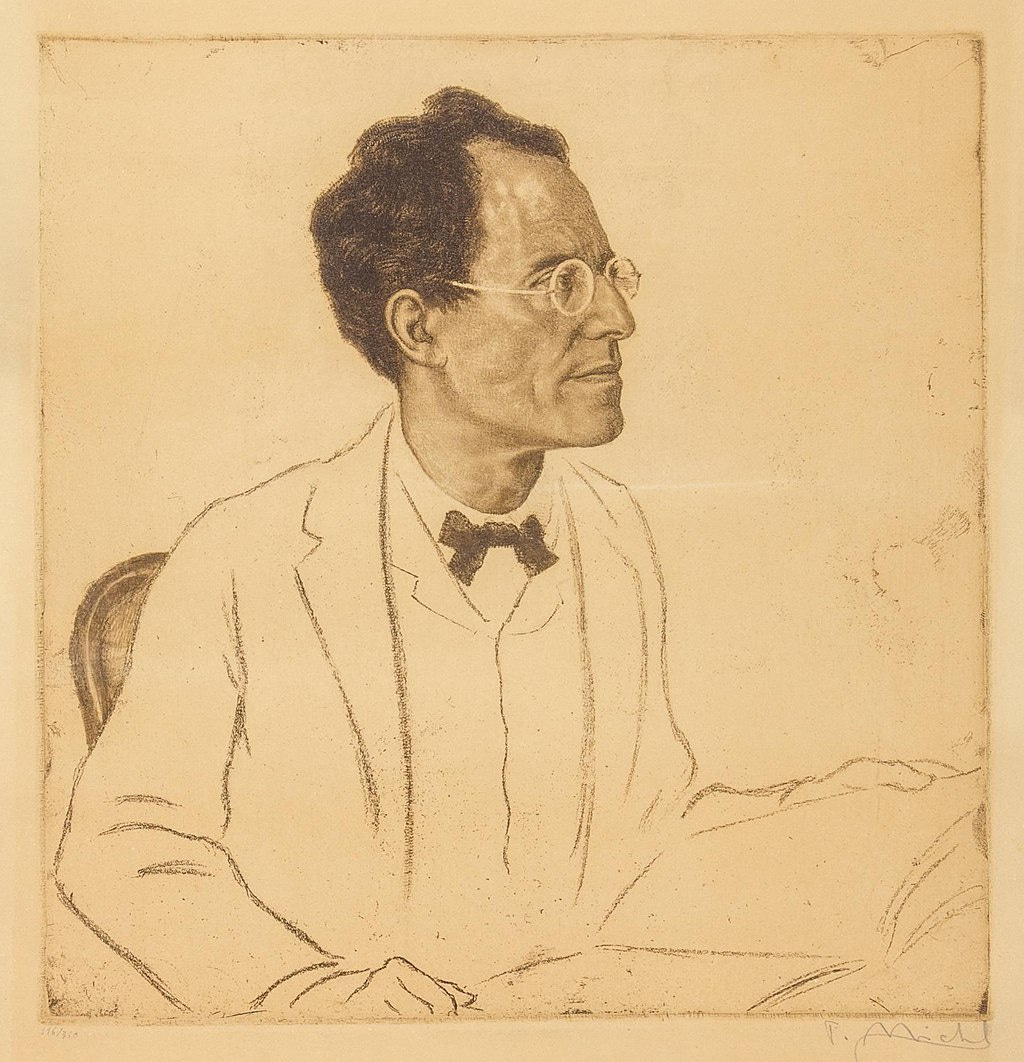

Of any of his symphonies, Mahler’s Seventh has provoked the most extreme range of reaction from those who know it. Deryck Cooke, the Mahler Scholar who created the performing version of Mahler’s Tenth Symphony, wrote that there was something irreductably problematic about the symphony, describing the finale in particular as a failure. Yet Cooke paused in his opinion to note that Arnold Schoenberg, not an unqualified admirer of the older composer and never an easy man to please, had, on hearing the first performance of the symphony in Vienna (not conducted by the composer), written to Mahler who was in New York in glowing terms. The letter of 29 December 1909 ended:

The impressions made on me by the Seventh ... are permanent. I am now really and entirely yours. For I had less the feeling of that sensational intensity which excites and lashes one on, which in a word moves the listener in such a way as to make him lose his balance without giving him anything in its place, [than] the impression of perfect repose based on artistic harmony; of something that set me in motion without simply upsetting my centre of gravity and leaving me to my fate; that drew me calmly and pleasingly into its orbit... Which movement did I like the best? Each one! I can make no distinction. Perhaps I was rather indifferent at the beginning of the first movement. But, anyway, only for a short time. And from then on, steadily warming to it. From minute to minute I felt happier and warmer. And it did not let go of me for a single moment. In the mood right to the end. And everything struck me as pellucid. I was in tune to the very end. And it was all so transparently clear to me. In short, I felt so many subtleties of form, and yet could follow a main line throughout. It gave me extraordinary pleasure.

Attempting to reconcile these conflicting views, Cooke hit on the unique quality of the Seventh Symphony, which marks it out from the others of Mahler’s cycle. Whereas in almost all else of his music, Mahler is driven by personal experience, the world and the process of spiritual self-discovery, the Seventh has no such impetus; there is no deep personal experience sitting behind the music, and it is Mahler’s only entirely abstract symphony, which undoubtedly heightened the appeal to Schoenberg.

If you would like to join the Salomon Orchestra, then please

email admin@salomonorchestra.org with your details and experience.

The Seventh Symphony was composed in an extraordinarily happy period of Mahler’s life, between the completion of the Sixth, which he claimed foretold three hammer-blows of fate falling on a hero, and three terrible blows striking Mahler himself. The Sixth was completed in the summer of 1904 while Mahler was on holiday at his summer home at Maiernigg in the Carinthian Mountains. In September, Mahler wrote the two short Nachtmusik movements, which became the second and fourth movements of the symphony, but then had to return to his duties at the Vienna Court Opera and composed no more until the following summer. Mahler returned to Maiernigg in 1905 but found that no inspiration came, subsequently writing to his wife Alma. “Not a note would come, I plagued myself for two weeks until I sank into gloom.... then I tore off to the Dolomites. There I was led the same dance, and at last gave it up and returned home.... I got into the boat to be rowed across. At the first stroke, the theme (or rather the rhythm and character) of the introduction to the first movement came into my head — and in four weeks, the first, third and fifth movements were done.” For his journey home, he took a train to Krumpendorf on the north shore of Lake Wörth and, from there, boarded the boat to be rowed across to Maiernigg.

The short score was finished on 15 August 1905, and Mahler then concentrated on the orchestration over the winter period, working before his day at the Opera House began, completing the work early in 1906. He then put the symphony aside to prepare for the premier of the Sixth in May 1906. The following year, the three hammer blows he described in the symphony struck Mahler, his daughter Maria died of scarlet fever, he was forced to resign from the Vienna Court Opera, and his acute heart condition was diagnosed.

Mahler was adamant in not promoting his own work in Vienna, and the Seventh was premiered in Prague on 19 September 1908, with the Czech Philharmonic Orchestra, at the festival marking the Diamond Jubilee of Emperor Franz Joseph. Alma recorded that he worked constantly on revising the orchestration during the long series of rehearsals and that his stamina and self-confidence seemed particularly taxed by preparations for the performance. “He was torn by doubts,” she wrote. “He avoided the society of his fellow musicians, which, as a rule, he eagerly sought and went to bed immediately after dinner so as to save his energy for the rehearsals.” Though the event generated considerable excitement, Alma reported that the piece had only a “succès d’estime.... The Seventh was scarcely understood by the public.” Indeed, this remained the case for nearly a century, and the Symphony has been very slow to win any acceptance.

The apparent contrast between the central movements and the finale has remained one of the most baffling aspects of the symphony. In a letter to the Swiss critic William Ritter, Mahler described the symphony thus “Three night pieces; the finale, bright day. As foundation for the whole, the first movement." The passage from dark into light can be seen as a journey from the cataclysm of the Sixth Symphony to something more hopeful which, if true, was, of course, dashed by the time of the premiere.

The first movement opens with Mahler's rhythmic oar strokes. A baritone horn states the first theme for which Mahler wrote, "Here nature roars." Unison horns then present a stirring march, which is by turns measured and impetuous. Violins introduce a yearning melody accompanied by sweeping cello arpeggios, leading to a reprise of the opening. Woodwinds and trumpets sound questioning calls over high trembling strings, while soft brass recall the march theme as a mysterious echo. A harp glissando ushers in a new development of the yearning violin theme, which is interrupted by a turn of the opening solo and is capped by a very high note for solo trumpet. The coda combines march themes and ends in an emphatic chord.

The first of the two Nachtmusik movements opens with two solo horns, the second muted in dialogue (the theme used once in a commercial for a well-known brand of engine oil). The movement is completely symmetrical around the central section. The horn calls are answered by skittering woodwinds, chattering amongst themselves. Distant cowbells are heard, and the horns introduce a bucolic theme, answered by strings and then woodwinds marked, “like bird calls”; the response is more rustic, but the central theme is darker, and as the movement unwinds, the final harp note leaves the music unresolved.

The Scherzo is marked Schattenhaft [shadowy] and in triple time, like a waltz, but far more sinister and spooky. The music opens with a strange pianissimo dialogue between timpani and pizzicato basses and cellos, answered by interjections from woodwinds. The nightmare quality is enhanced by Mahler’s vivid orchestration, fragmentary instrumental solos contrasted with a recurring timpani motif. The central trio section is warmer, with a motif introduced by oboes that descends through the whole orchestra. The nocturnal dance resumes and winds sepulchrally to a close, ending with a final drum stroke and brass chord.

The second Nachtmusik, marked Andante amoroso is altogether gentler, a reminder that night, as well as being dark and menacing, can be magical and affectionate. Trombones, tuba and trumpets are silent, and Mahler reduces the woodwinds to soloists making chamber music, like a Viennese serenade. A solo violin opens the music, and a solo horn intertwines with guitar and mandolin to enhance the intimate character. The menace is not altogether banished, the harmony remains dissonant, and the intimacy fragile. The music closes with a gently trilling clarinet.

After the calm of the fourth movement, the intrusion of Mahler's "bright day" finale is an abrupt shock. A dramatic timpani solo heralds blazing full brass, The Rondo form allows Mahler to present a series of apparently unconnected themes and sections which contrast dramatically with each other. Much has been made of the allusion to Wagner’s Die Meistersinger, (the opening chorus in Act I, and also at the end of the final version of Walter's Prize Song sung in Hans Sachs house). An apparent allusion to Lehar’s Merry Widow Waltz is less certain, since both composes were working at the same time (1905). Eventually, the march theme joins with the fanfare to come to a resounding climax, with pealing bells and rolling drums. The contrasts of the entire symphony make their final appearance in the resolution of the penultimate chord. Mahler throws one last challenge on the final page, a seemingly random change in the harmonic quality from major to augmented; the music suddenly drops to piano before a defiant fff major chord ends the work.

Programme notes provided by Dominic Nudd, October 2018 via MakingMusic