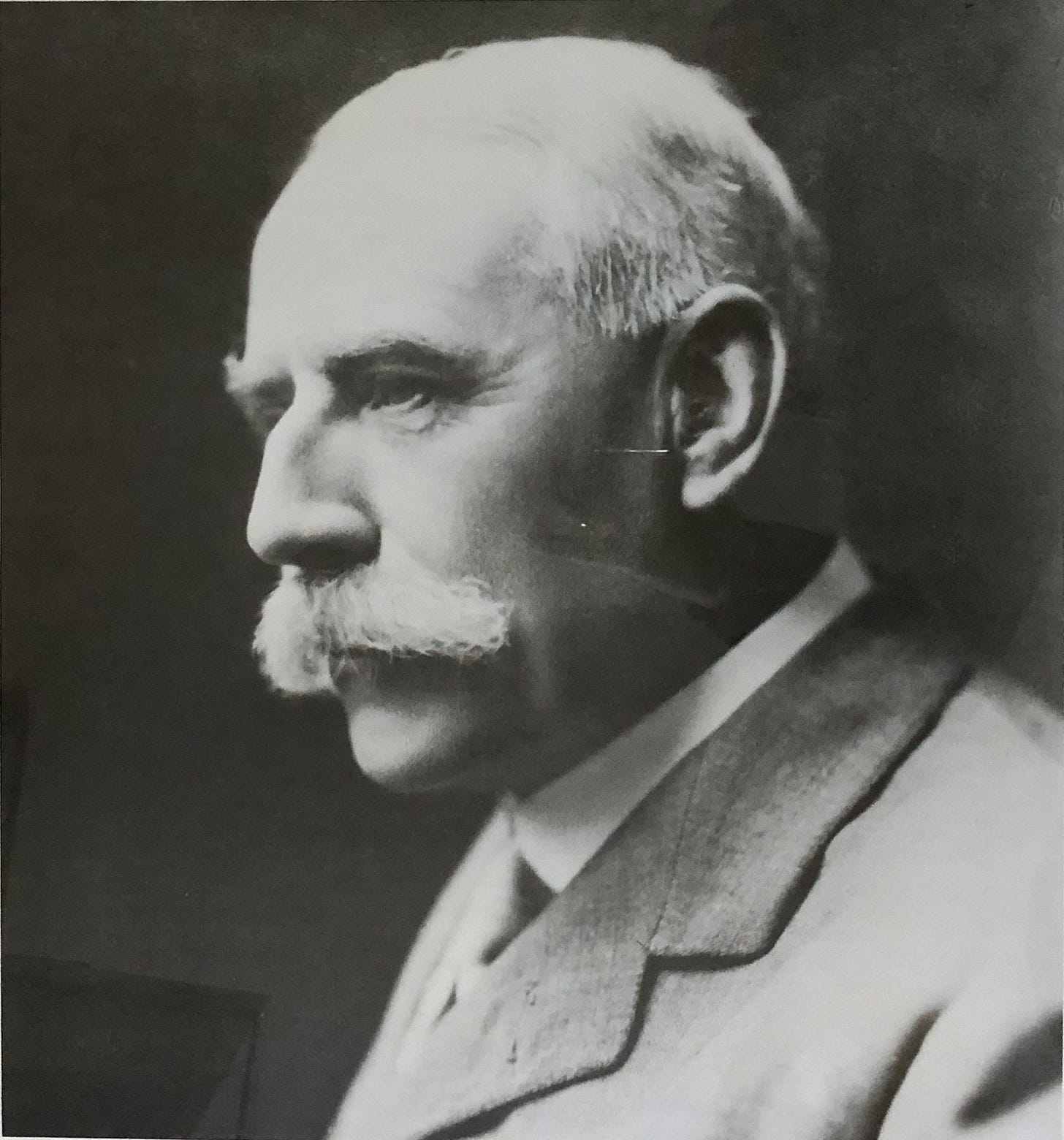

Image Credit: The Elgar Society (https://www.elgarsociety.org)

Symphony No. 1 in A♭ major, Op. 55 is the first of Edward Elgar's only two completed symphonies. Lasting 45-50 minutes and scored for a large orchestra, the symphony was dedicated "To Hans Richter, Mus. Doc. True Artist and true Friend.". Richter conducted the premiere on the third of December 1908 in the Free Trade Hall, Manchester and was unequivocal about its merits. "It is the greatest work", he said, "of the greatest composer alive in any country."

Ten years before composing his first symphony, Elgar had been intrigued by the idea of writing a symphony to commemorate General Charles George Gordon. As he passed his 50th birthday, he turned to his boyhood compositions, which he reshaped into The Wand of Youth suites during the summer of 1907, but also started to work on a symphony, finishing the first movement while in Rome for the Winter. After his return to England, he worked on the rest of the symphony during the summer of 1908.

By this time, Elgar had abandoned the idea of a "Gordon" symphony in favour of a wholly non-programmatic work. He had come to consider abstract music as the pinnacle of orchestral composition: he thought music was at its best when it was simple, without description. He wrote to the music critic Ernest Newman that the new symphony had nothing to do with Gordon and to the composer Walford Davies, "There is no programme beyond a wide experience of human life with a great charity (love) and a massive hope in the future."

If you would like to join Salomon Orchestra, then please

email admin@salomonorchestra.org with your details and experience.

It was widely known that Elgar had been planning a symphony for more than ten years, and the announcement that he had finally completed it aroused enormous interest. The critical reception was enthusiastic, and the public response was unprecedented. The symphony achieved immediate and phenomenal success, with a hundred performances in Britain, continental Europe, and America in just over a year of its première.

Samuel Longford wrote in the Manchester Guardian that: "... the work is the noblest ever penned for instruments by an English composer, we are quite certain". The Daily Telegraph reported that: "After the extremely beautiful & poignantly expressive slow movement, the composer was called onto the platform several times to take a bow by a crowd that was almost beside itself with enthusiasm. Again, this scene was repeated at the close and from none was the applause more hearty than from the orchestral players themselves."

Four days after the Manchester performance, Richter gave the London première with the LSO and, at the first rehearsal, greeted the players with the words, "Gentlemen, let us now rehearse the greatest symphony of modern times, and not only in this country". The Anglo-German publisher and Elgar's friend August Jaeger, who had been too ill to travel to Manchester, attended and described the event:

"I never in all my experience saw the like. The Hall was packed; any amount of musicians . . . the atmosphere was electric. After the first movement E.E. was called out; again several times after the third and then came the great moment. After that superb Coda (Finale) the audience seemed to rise to E. when he appeared. I never heard such frantic applause after any novelty nor such shouting. Five times he had to appear before they were pacified. People stood up & even on their seats to get a view."

The Music Times printed a digest of press comments on the symphony. The Daily Telegraph was quoted as saying, "[T]hematic beauty is abundant. It is exquisite in the adagio, and in the first and second allegros, the latter a kind of scherzo; when the rhythmic impulse, the power and the passion are at their extreme height, when the music becomes almost frenzied in its superb energy, the sense of sheer beauty is still strong." The Morning Post, wrote, "This is a work for the future, and will stand as a legacy for coming generations; in it are the loftiness and nobility that indicate a masterpiece, though its full appreciation will only be from the most serious-minded; to-day we recognise it as a possession of which to be proud." The Evening Standard said, "Here we have the true Elgar – strong, tender, simple, with a simplicity bred of inevitable expression. ... The composer has written a work of rare beauty, sensibility, and humanity, a work understandable of all."

Its success was not guaranteed, of course. The public success of the Enigma Variations and Cockaigne Overture raised high expectations for any possible symphony from Elgar. Like Brahms before him, Elgar was acutely aware of this interest and expectation and was deeply nervous about not meeting his own high standards and the expectations of others, so he was extremely cautious about committing himself to writing a symphony. However, the more he delayed, the greater the sense of expectation was provoked, especially as he occasionally let slip public statements about a possible symphony which never subsequently materialised.

Another factor in Elgar's caution may be that, at the time, the symphony was seen as being in decline. In 1905, Elgar was Professor of Music at Birmingham University and, in one of his lectures, said:

"I hold that the symphony without programme is the highest development of art…it seems to me that because the greatest genius of our days, Richard Strauss, recognises the symphonic poem as the fit vehicle for his splendid achievements, some writers are inclined to be positive that the symphony is dead. . . perhaps the form is somewhat battered by the ill usage of some of its admirers, . . but when the looked-for genius comes, it may be absolutely revived. "

Three years later, Elgar himself was seen as the looked-for genius, and the form was, indeed, revived.

If you would like to join Salomon Orchestra, then please

email admin@salomonorchestra.org with your details and experience.